Table of Contents

Modern agriculture faces increasing uncertainty. Extreme temperatures, seasonal limits, and unstable weather directly affect crop growth and yield consistency.

A temperature controlled greenhouse addresses these challenges by turning temperature from an external risk into a managed variable. It is not just a covered structure, but a system designed to maintain a stable growing environment across different seasons and climates.

The Physics Behind Evaporative Cooling

Evaporative cooling is based on a simple physical process called phase change.

When water changes from a liquid to a gas, it requires energy. This energy is called latent heat. During evaporation, water absorbs heat from the surrounding air. As heat is removed from the air, the air temperature drops.

Raising the temperature of water by 1°F requires only about 1 BTU of energy. But turning that same water into vapor requires about 1,060 BTU per pound. This large energy transfer is what makes evaporative cooling effective.

Unlike air conditioning, evaporative cooling does not create cold air. It removes heat from air by using water evaporation. Fresh air must continuously move through the system for cooling to continue.

Why Evaporative Cooling Is Different from Air Conditioning

Traditional air conditioning systems use refrigerants and compressors. They cool air in a closed loop and recycle indoor air.

Evaporative cooling systems work in an open loop. They rely on constant air exchange. Warm outside air enters the space, passes through water or mist, loses heat, and exits through ventilation.

Because of this, evaporative cooling systems consume far less electricity. But they depend heavily on outdoor air conditions.

Humidity Is the Key Factor

Humidity is the most important factor in evaporative cooling performance.

Dry air can absorb more water vapor. This means evaporation happens faster and removes more heat. In dry climates, evaporative cooling can reduce air temperature dramatically.

In humid air, evaporation slows down. When air is already close to saturation, very little additional water can evaporate. Cooling potential drops sharply.

For example, at an outdoor temperature of 90°F (32°C):

At 30% relative humidity, evaporative cooling may reduce air temperature to around 67°F (19°C).

At 70% relative humidity, the temperature may only drop to about 82°F (28°C).

This difference explains why evaporative cooling works well in dry regions but performs poorly in hot and humid climates.

In humid environments, excessive moisture can also cause problems. High humidity increases disease risk and may reduce plant transpiration. In some cases, evaporative cooling can stop working entirely.

Main Types of Evaporative Cooling Systems

Evaporative cooling systems are not all the same. Each type has different strengths and limits.

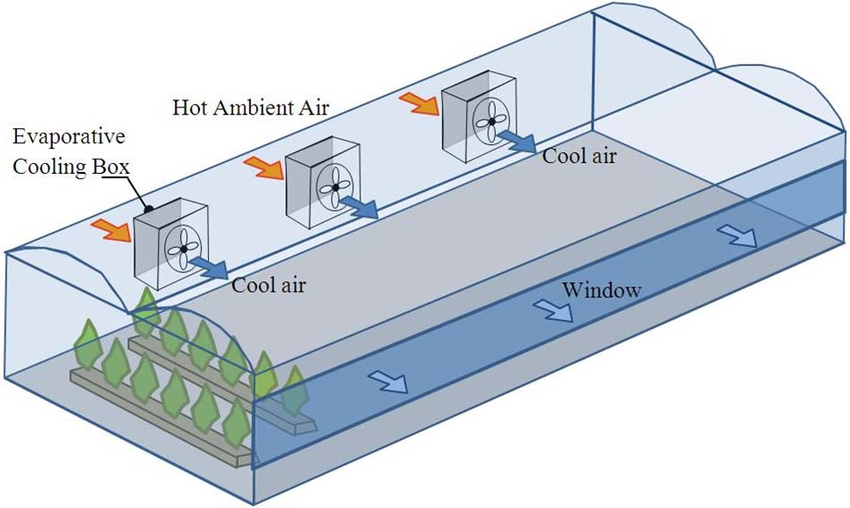

Fan and Pad Systems

Fan and pad systems are the most common evaporative cooling method used in greenhouses.

Cooling pads are installed on one side of the structure. Exhaust fans are installed on the opposite side. Fans pull hot outside air through the wet pads. As air passes through the pad, water evaporates and cools the air before it enters the space.

This system has been used for decades. It is reliable and well understood. It works best in long, narrow buildings with strong airflow from one end to the other.

Fan and pad systems require good maintenance. Pads must stay clean and evenly wet. Airflow must be correctly sized to avoid hot spots.

Please leave your contact email, and one of our professional greenhouse engineers will reach out to you within 24 hours.

High-Pressure Fog Systems

High-pressure fog systems spray extremely fine water droplets into the air. These droplets evaporate while suspended, cooling the air directly.

This method produces very uniform cooling. It avoids strong airflow patterns and reduces temperature gradients.

Fog systems are well suited for propagation areas and high-precision environments. They require clean water and high-quality filtration. Poor water quality can clog nozzles and reduce performance.

Humidity control is critical. Fog systems must be carefully managed to avoid excessive moisture buildup.

Portable or Swamp Coolers

Portable evaporative coolers are self-contained units. They combine a fan, water reservoir, and cooling media in one device.

They are easy to deploy and suitable for small spaces or local cooling zones. However, they offer limited control and are not suitable for large or tightly controlled environments.

These systems are best used as temporary or supplemental cooling solutions.

Engineering Design and Sizing Principles

Evaporative cooling must be designed as a system. Random installation rarely works well.

Airflow is the first critical parameter. Cooling capacity depends on moving enough air through the space. In greenhouses, airflow is often designed based on cubic feet per minute (CFM) per square foot of floor area.

Cooling pad size must match airflow. If pads are too small, air moves too fast and does not cool efficiently. If pads are too large, resistance increases and airflow drops.

Water supply must be stable and evenly distributed. Evaporative cooling does not mean spraying large amounts of water. Pads and fog systems must stay uniformly wet without dripping.

Water storage capacity should allow continuous operation without interruption. Running dry can damage pumps and reduce cooling effectiveness.

Design calculations should always prioritize airflow first, then pad area, then water flow.

Integrated Cooling Strategies

Evaporative cooling cannot operate alone.

Ventilation is essential. Without proper exhaust, cooled air will not move through the space. Stagnant air creates hot zones and humidity pockets.

Shade systems play a major supporting role. Reducing solar heat gain lowers the cooling load and improves system efficiency.

Control logic is also important. In many systems, fans should start first. Water should only activate when airflow is established. This prevents unnecessary humidity buildup.

Automated controllers can link temperature, humidity, and cooling stages. This coordination improves stability and reduces operator error.

Maintenance and Troubleshooting

Long-term performance depends on maintenance.

Algae growth is a common issue. Light exposure combined with water promotes biological growth. Shaded water lines and regular cleaning help reduce this problem.

Water quality must be monitored. Minerals and salts can accumulate in recirculating systems. Bleed-off or periodic flushing is required to prevent buildup.

Seasonal management is also important. In cold months, evaporative cooling systems may need to be drained, shut down, or removed to avoid freezing and damage.

Conclusion: When Evaporative Cooling Makes Sense

Evaporative cooling is a powerful and efficient cooling method. It uses simple physics and very little energy.

However, it is not a universal solution. Its success depends on climate conditions, correct design, and proper integration with ventilation and shading.

When humidity is low and airflow is well managed, evaporative cooling can transform a hot structure into a productive growing environment. When applied without understanding its limits, it can create new problems instead of solving old ones.

The key is not the technology itself, but how and where it is applied.